At first, the gongs were irritating. Periodic thunderous blasts from the third floor of a museum can disturb one’s focus on an art display if one is simply trying to establish their footing. However, as I plunged deep into the content of the Rubin, I noticed that these gongs worked in concert with the art to transport me into a meditative realm. I stood before every painting for minutes, not only observing its details but participating in a conversation with the artist. Rather than being unshackled from my own experiences and values, I brought all of myself to this dialogue in order to meaningfully interact with and extract as much possible value from the pieces of art on display. For the first time in my life in an art museum, I took the time not merely to gallop from piece to piece like I was in some kind of buffet, but to absorb the meaning of the paintings, let such thoughts ruminate and reflect.

The Rubin does a remarkable job of assembling a collection of pieces which encompasses those which are a millenia old to those which were literally made in the last few years.

One of the contemporary pieces which resonated with me was that of New World by Roshan Pradhan (2021). I am as much of a fan of technological progress as anyone. I don’t fear the gears or the robot bees depicted in this painting and I think the background of large columns suspended in the sky conveys that any kind of future society that employs robotic technology will be high-achieving and heavenly in its standards of living. However, this painting evokes my dread of the robotic era because it emasculates me, the male viewer. The robot in this painting assumes a dominant sexual position and provides the ultimate erotic satisfaction to the woman whose legs are wrapped around him. He also produces offspring which swim through the body of water below him. It is one thing for humans to use increasingly advanced robots or even to be replaced entirely by robots in the far future. However, this painting presents me with the terrifying prospect of competing directly with robots-which means inevitable failure and subjugation. I face no chance of success in the sexual marketplace against a machine designed for stimulation. Nevertheless, the robot of New World has not only bested me in pleasing a beautiful woman but while shoving this in my face, he parades around his robotic bloodline of superior humanoids. Thus, the robot has not only defeated me but his children will one day rule over my children in the same fashion.

In this painting, there is a glimpse of the robot’s threat to take away what gives men like me meaning, which is to be a magnetic figure who attracts and inspires. The kind of force of personality required to seduce and satisfy is something one would never think to ascribe to a robot, which our culture views as stiff and emotionless. Nevertheless, New World imagines that we have entered a phase of progress where robots thrive in the sexual sphere. This means they have acquired a liveliness that is all-too-human and which threatens the sexual monopoly which human men currently enjoy with women. However, even beyond romantic partners, the robots threaten to outperform men in the masculine charm which is used to attract them. The loss of exclusive control over such an aura-the product of self-assertiveness and heroism-means the loss of animating energy for many men. This new world is petrifying because the human man is absent from the picture, just as he is nowhere to be found in this painting. Men are not present in this concocted dystopia because they have been surpassed by a race of charismatic robots.

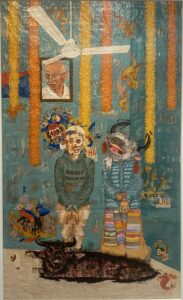

A second work of contemporary art which I connected with at the Rubin is A Crime with Mother by Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee (2022). The subject of this painting wears a sweatshirt with an American rock song. Half of his head has been transformed into a skull because he feels he has committed a great moral evil by consuming meat. I do not know what it’s like to treat vegetarianism as a religious or legal obligation as opposed to a personal commitment. However, I do feel connected to a universal theme that this painting touches on, which is managing the guilt and social consequences of assimilation. If this painting had replaced the cow with a pig, I would have believed you if you had told me that it was created by a Jewish artist. That is because there was somewhere in my own familial line where someone had to contend with whether or not they would consume a non-kosher diet in America. I don’t feel like I am worthy of death when I consume pork, but in my community certain lifestyle choices that depart from the Jewish tradition feel unethical. For instance, I would feel a moral blight if I married outside of my faith.

The blackness of the dead cow and its face’s fearful expression are chilling. These sights make the viewer feel the moral cost that is weighing on the painting’s subjects. The cow’s fright is burned into the minds of those who consumed him. I wouldn’t know how to artistically render-in as poignant a manner as this startled cow-the blameworthiness I’d feel at ending my long-line of Jewish ancestry. That may be because it is not as easy to pinpoint the victims of Jewish intermarriage as those of meat-eating, since the injured party is not right on your plate.

The young man and his mother also wear handcuffs because eating meat is illegal. This artistic choice alludes to the maltreatment imposed by a community upon a “sinner.” In the case of intermarriage, many families and synagogues will engage in social ostracization and treat the intermarried person as an outcast. These externally imposed costs would probably be more painful for me than any moral qualm I had with my behavior because of how critical these social bonds are to the quality of my life.

The photo of Gandhi hanging on the wall, staring at the mother and son with a judgmental expression, is reminiscent of the photos of rabbis which are on the walls of Jewish households like my own. The rabbi serves as a symbol of one’s spiritual and communal identity. Gandhi’s affect here implies that the picture’s orientation changes based on the household’s loyalty to religious doctrine. If the subjects of the painting had sacrificed their own pleasure and not consumed meat, Gandhi would’ve been a source of pride and smiled lovingly at them. However, to see Gandhi in the midst of their sin only compounds the feeling that they have betrayed their moral compass and he glares at them like an ashamed father.

I was perplexed by the mother’s buffalo head. Although in one sense, she may be hiding behind a disguise, the mask itself is unsettling. It looks like a murderer’s attire-the kind that one would only expect to see in a horror movie. One way to interpret this costume is that just as the son in the painting has a partly skeletal face because he believes his actions have made him akin to Death himself, the mother feels she resembles a killer so senseless that they would wear their victim’s body parts on themselves. The painting is not realistic, but seeks to portray how the mother and son genuinely feel about their actions.

The Rubin Museum also provides a wealth of art depicting Hindu Gods and Goddesses which I was able to explore on a whole new level. One such piece of art is the Two-Sided Festival Banner of Varunani and Varahi from 17th/18th century Nepal.

I have very little experience with Hinduism. Their Gods are completely foreign to my own religion of Judaism, which is a transcendent monotheism that views depictions of God as a grave affront. On their face, the Hindu Gods resemble refined and powerful animals to whom one prays for protection. This image could confirm that presumption. However, I sought to discover the message communicated by this work of art using its elements alone without any prior knowledge of Hindu teachings.

The Hindu Gods appear to be worldly, which is usually a pejorative characterization in a religious context, but I mean worldliness to be a positive attribute in that the Gods symbolize and inspire material success. Varahi’s attire is elegant, including her robes, foot jewelry, crown, earrings and bracelets. Rather than merely being described as immensely powerful, she is shown to be, as she has many arms and holds a scepter in one of them. Her multiple arms demonstrate that she has the ability to accomplish many things simultaneously and her scepter reveals that she wields earthly authority.

I had the most difficulty understanding how such a glamorous goddess could be a red boar. The answer I take from this painting is that there is a kind of ruthlessness, which is animalistic and evoked by the bloody tint of red, that may be at times required for worldly success. In a dog-eat-dog world, self-preservation involves getting one’s hands dirty. When I think of a boar I think of a creature that will do anything to get its food and that is why this goddess is not any old goddess. She is a beautiful boar goddess.

As a person who would like to succeed in the rat race, Varahi provides me with inspiration. To worship her means to worship the ideals she embodies, which include the acquisition of power and wealth. A goddess like this is a breath of fresh air from the other-worldliness of my own religion and Christian culture which says that moral goodness necessitates withdrawal from the world. Varahi uses her wealth and power not merely for her own glory but also to protect her worshippers. She teaches us the priceless lesson that whether we are trying to improve the quality of life for ourselves or others, we need to act within the real world and the system we exist under in order to make tangible improvements.

Another set of works at the Rubin which shed light on Hinduism and its departure from Judeo-Christian culture were sculptures like the one above, Chakrasamvara In Union With Consort Vajravarahi from 14th century Tibet. The sculpture depicts a god and goddess in loving embrace and trampling upon another supernatural duo. I was flabbergasted when I saw these figures because my experience with religion has been that intimacy and dominion over others are things which should not be glorified. To exert domineering power over others in western culture is a mark of cruelty and exploitation. Additionally, intimate sexual acts are meant to be private. Even if these things are not viewed negatively, they are not meant to be idolized. I see great bravado in the artist’s choice of subject. Not only are these gods crowned with Jewels and carrying the symbols of power but they are displaying their power to all. I feel exhilarated as I look at this sculpture and am met with a romance. This sculpture does not facilitate a one sided interaction between the female subject and the male spectator. There is complete sexual participation by each party, which makes the work feel even more invigorating. I see in this divine pair a vibrant relationship and a true power couple: a paragon of love and success. With fire blazing in the background, I am electrified by the thought of dancing away the night with the love of my life as my competitors falter beneath me.

I would like to compare what I came to see in the Rubin as the traditional Hindu depiction of the Gods and one of the contemporary works which missed the mark. One of the pieces that I adored was Durga Killing The Buffalo Demon from 13th Century Nepal and one which I did not care for was Compassion by Jasmine Rajbhandari (2023). I loved the sculpture of Durga, like many of the other Hindu pieces, because of her vitality. She has triumphed in battle; she is elegant and wealthy; she has a multitude of limbs-some of which carry weapons-conveying her versatility. Durga is the ultimate expression of the worldly glory that human beings can aspire to, which is found in her military victory, material gains and her success in multiple areas of life.

On the other hand, Compassion portrays the Gods as healers or providers to victims of warfare. I absolutely believe in emulating the selflessness of the Gods. However, this feels like an inversion of what individuals ought to take from Them. People should not be dependent on deities. The consequence of that mindset will be feebleness and ineptitude. War is an exception in that people cannot provide for themselves. However, the greatness of the Gods, which is supposed to inspire people to action, is displayed as assisting the weak. This creates a subliminal lack of agency on the part of the viewer. The viewer will feel justified in awaiting the aid of the Gods, as opposed to their acting as role models for human achievement.

One of the striking ways in which the divergence between strength and weakness is illustrated by the visual differences in the paintings is the gendered characteristics of the Gods. Durga is sculpted as a powerful woman with accentuated female features. The protagonists in Compassion are enlivened, androgynous statues. The result is that one of these artworks feels more human. It is difficult for me to feel a connection to alien-like floating beings. However, sex is a defining human characteristic and plays a vital role in establishing human identity. What Hindu Gods can do well is capture the greatest hopes and dreams of every young person. However, even if such a person’s dream was to be the greatest caregiver there ever was, there is little to latch onto in Compassion. The viewer is an outsider observing a foreign species helping those who cannot help themselves. With Durga’s statue, even a young male is rejuvenated with energy seeing a female goddess place all of her effort into becoming the top dog.

There were two pieces from the Rubin to which I would apply the colloquial use of the term “modern art.” Goddess of Tangerine by Kunsang Gyatso (2023) appealed to me while The Womb & The Diamond by Charwei Tsai (2021) felt ineffective. One of the reasons these works are “modern art” is that in both one has to learn from elsewhere the context and story behind the pieces in order to appreciate them.

Goddess of Tangerine imagines a reality where the tangerine is worshiped because the fruit is on the verge of extinction. It is outlandish and at first I was going to write it off as absurd. However, while one has to do mental legwork to gain some profound meaning from the work-also conventional wisdom about modern art-there were insights that the piece brought forth and made clearer to me. One is the idea that everything will decay and die, or impermanence. This was signified by the physical tangerines which are displayed at different stages of their life cycle. I meditated on the idea that I, like a tangerine’s bright orange, am now youthful and strong but I will gradually lose my vigor and robust frame until I turn into nothingness. This sentiment empowers my ego and drive. If tomorrow is not guaranteed, then I must strive for greatness today. Additionally, the work invites the viewer to question why certain things are worshiped. I found myself asking, why do we worship things which are rare? Aren’t the most beautiful things, like love and God, those things which are universally accessible? Something can be precious and worth appreciating without it being rare. However, people often worship those things which are rare and assign them a high monetary value even though they may not be of any intrinsic worth. In the case of the tangerine, it is being worshiped because it is on the brink of extinction and contributes essential value to the ecosystem. There is a dialogue and a story to interact with in Goddess of Tangerine, even if one has to read them on the plaque first.

In the case of The Womb & The Diamond, I felt no connection to the ideas that the artist intended to represent. As I learned from the plaque, there was a lot of blowing and recitations which went into making all of the glass bubbles and tiles. The shapes look alike and so they’re supposed to represent interconnectedness and the universal potential of every human being to achieve nirvana. My feeling is that this is a completely one sided art endeavor. There was a lot of intentionality which went into the work but none of that is known to the audience. In addition, I feel as though interconnectedness should be based on something more substantive. Shouldn’t such a profound idea be inferred from something other than a bunch of identical shapes? If I were to make many different glass squares or paper triangles which all looked the same, would that also represent interconnectedness?

In summation, the substance of Goddess of Tangerine had to be given to the audience but felt meaningfully connected to the artwork. In contrast, The Womb & The Diamond not only required a background, but its message lacked a concrete connection to the work itself.

To conclude, I had a phenomenal trip to the Rubin. I traveled with another student and ended up staying from eleven to four (the museum’s hours are eleven to five). My peer explored the whole museum, went out to eat and to the park and all the while I was still in the museum basking in the art. It was an unbelievable opportunity to explore non-Western art and dive deep into other religions and cultures. For the first time, I acquired my own sense of what Hinduism is about. I was also able to connect with universal themes like coping with assimilation and recognize trends in artistic style-like “modern art”-in works which come from an entirely different area of the world. I realized that no matter the country in question, the most fundamental human ideals lie at the heart of artistic expression.